This is an entry from my series of horror movie a day write-ups and viewings. I excerpted it because, well just because.

This is kind of a new thing for my horror movie a day ritual I’ve been writing through(Day 29!), in that I’m actually re-watching something I’ve already seen. But this week I watched the incredibly brilliant, and worth your 5 bucks, lecture on the New French Extremity by Alexandra West (of the also brilliant faculty of horror podcast). I realized even more than ever how much affection I have for these films, particularly the horror off-shoots. It was also really interesting to me because Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day was placed within this movement which for some reason I had never really thought about.

Trouble Every Day is a film directed by Claire Denis, starring Alex Descas, Beatrice Dalle, Vincent Gallo, and Tricia Vessey. It is the story of two couples whose lives have are infected by this horrible virus which causes Gallo and Dalle to crave blood and human flesh. It is a story about science, nature, men, women, disease, space, vampirism, hysteria—all of these things.

I saw Trouble Every Day before I was cognizant of the New French Extremity Horror films. I remember when I first watched it, it was I think the spring of 2002, because it came out in May of 2001—and I remember watching it in my college dorm room, I guess this would have been my freshmen year, and I was such a baby then. I hadn’t come out yet, and in terms of film, netflix and the internet had both gotten to the point to where I could really fall down through film history at that time. My school was also right across the street from a blockbuster—and I remember I would get out of class on one end of campus, and then with my headphones on and hood up, walk the length of the campus to the Blockbuster to get a new movie—and I remember sometimes I would even be sick with fever, and still feel that walk was worth my while.

So what I’m saying is I saw this film long before I could ever sort of understand it in any context, but also during an extremely formative time personally. My mom and step-dad had gotten divorced, 9/11 happened, my dad who had been against me going to college was terrorizing me via email such that I completely cut him out of my life. I also had my first major suicide attempt that fall—where I completely mutilated my right arm—but in the end didn’t rupture anything enough that I got sent to the hospital, and in fact, it would be two more years before I would actually get committed after another botched attempt, this time involving sleeping pills.

When I think about Trouble Every Day, I think very much of this time. And I remember too, that one of the reasons I was so rabid to see it is that I had an incredible crush on Vincent Gallo after Buffalo 66, and then getting into his music, and his art, and the things he would write or say—his perrrrfect body and eyes…maybe I do still have a huge crush on Gallo(maybe nothing!). I actually watched that terrible movie he made with Courtney Cox—like I pretty much tried to watch whatever looked like a decently sized role for Gallo at the time. Which led me to Trouble Every Day which also starred Beatrice Dalle who I knew from Betty Blue, and who I knew before I knew Charlotte Gainsbourg, or before I knew Isabelle Adjani—I find these women in their films express often things that I feel inside of myself, but feel too strangled by my own body and mind to be able to articulate.

I say these things intending to get the point where I talk about Trouble Every Day—but I think even though it is all unimportant in the end, I think that the way that art can form a life long symbiotic relationship with you is one of the more addictive properties which exceed art’s properties towards the sublime. Maybe it is the relationship of the post-sublime—the shadow of the great experience, that you carry yourself under forever and ever until you go mad.

So it was really interesting to come back to this film. I don’t know that I’ve even watched it in full since the early 2000s. I used to have a bootleg copy of the film because for the longest time I don’t think it was really available. I also had an imported copy of the Tindersticks soundtrack.

It’s interesting to come back around on Trouble Every Day post-Possession, and post the rest of the New French Extremity of Horror. I remember at the time, I was somewhat ashamed by my inability to articulate why I loved this film, or maybe I was ashamed that I loved it. Much of the critical writing I had access to at the time absolutely blasted the film, and it is not the kind of film you test on mixed company when you are young and uncertain. Particularly if you are closeted and part of your analysis is just wanting to jump Vincent Gallo’s bones.

Watching it now as a slightly more developed human(or maybe less developed—who knows)—I’m struck by just how powerful the film is. Even after all of these years. In fact, my experience watching it today, may have even been more invigorating. Agnes Godard absolutely paints this film. Her color palette, composition—it has this restrained consideration—she just creates this coolness which is also sharp edged and violent—but it is not the sensation of violence as a staccato rhythmed punchline. Godard shoots the body like a landscape, and violence like a slow-moving thunderstorm moving across the plains.

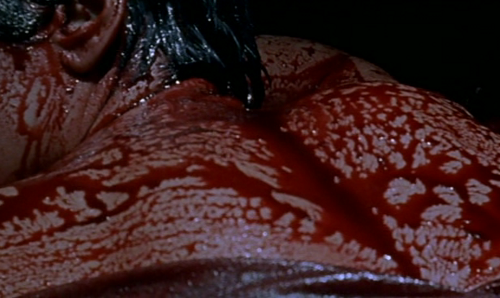

There is a scene in this where Dalle is having sex with this boy who has broken into her room and the way the camera moves languidly up and down the boy’s body—his flesh this dappled pink and red with oasis’s of hair pooled around his arms and chest—and the way that Dalle presses her flesh into his, is like watching a python constrict around a lamb. And almost imperceptibly the scene shifts from something as beautiful as two people finding a peace between themselves—to apocalypse. Dalle starts eating the boy’s flesh, eating him piece by piece, his screams mirroring orgasm at first, before turning into complete horror. The way that she chews up his face, keeping him alive listening to the rattling of his breath, slapping his skin to keep the blood flowing—it is what I mean when I saw that true beauty is horrific. If you can watch the scene without turning away, it is something you will never be able to see expressed this well.

Dalle is communicating this insatiable hunger, this pain that makes her want to die every second of her life with this disease—finding the release that her husband doctor denies her, and the boy who came up the tower to rescue the princess, who came up the tower to fuck the princess, who thought that he knew her pain—he enters this house, he breaks into it, thinking he understands what it is she wants. He thinks that she wants what he can give her, which is true—but not in the totality of her terms. The totality of her terms is not something he can bear or that his body can survive.

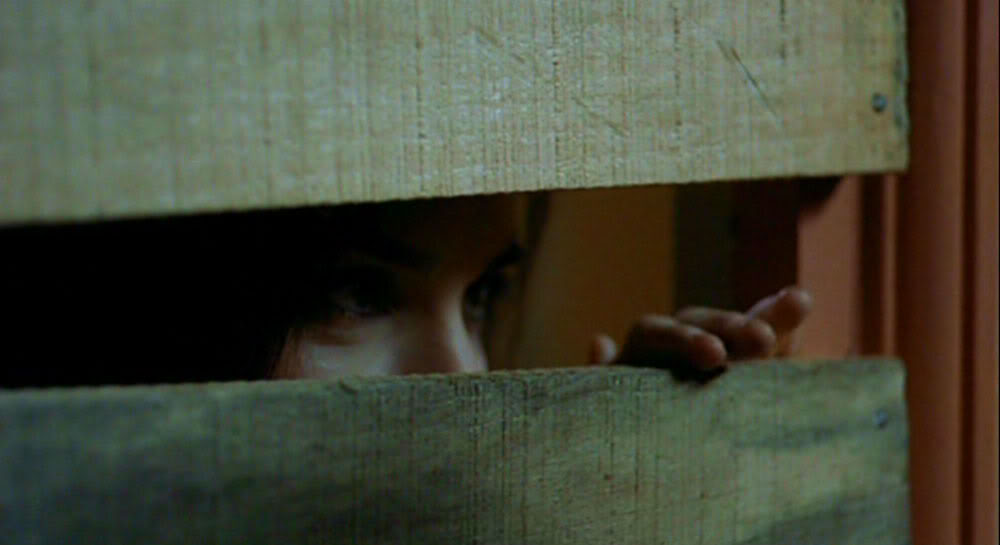

One of the great performances in this film, besides Dalle and Gallo is the doctor played by Alex Descas. It is his creation which has infected both Dalle and Gallo—and he is so horrified by what he has done to his wife, what he has found in her, that he has to board her up in the attic. Which is of course the archetype going back to at least Jane Eyre and then later the Yellow Wallpaper.

What’s interesting with Descas is that he absolutely has no control over Dalle. He locks her behind boards, and metal bars every night—he gives her pills that she does not take. Every night she escapes and kills. Every night he goes out, and hides what she has done, and then locks her up again before leaving her alone in her prison that he has made for her. But this prison is only the illusion of his control. The idea that his science can control her nature.

The bars themselves are a defeat for Descas. He is a man of science, and for all of his science he has to resort to bars and boarded up doors. Dalle asks him to let her die, to let her end the agony she experiences, and the monster she has become. But even that he cannot do. His own hubris won’t allow him to admit defeat to her nature. Beyond that, I think that his love for her is another cage he has built for her. He loves her, but only on his terms. On the safe grounds where he feels that he has control and can avoid contamination. He won’t give himself over to her fully. This is deep fucking tragedy.

Descas and Dalle are mirrored against another couple played by Vincent Gallo and Triccia Vessey whose situation is somewhat reversed, but a lot of the same issues come to the fore which I think illustrate that it isn’t merely Dalle’s illness that is the core of this horror, but rather man’s relationship to woman.

With Gallo and Vessey, it is Gallo who has the virus and the insatiable blood lust. He has just married Vessey, and they have come to Paris for their honeymoon, though secretly it is also for Gallo to try and find Descas so he can hopefully find a cure for his disease. Gallo is absolutely petrified of losing control and either infecting or killing his wife. At one point he is locked in an airplane bathroom fantasizing about Vessey covered in blood.

As with Descas, Gallo’s issues are those of control. Though he doesn’t lock Vessey up in an attic—he locks her away from himself in every way that matters—in fact over and over again when he is faced with the possibility of giving up his control over to Vessey he has to run and lock himself in a bathroom. Gallo like Descas is a man of science, and as with Descas he seeks to deny his nature, to control it with locks and bars—and as with Descas both end up hurting the woman they are in love with.

There’s a great scene where Gallo and Vessey are about to consummate their marriage, and right before Gallo gives over—in a scene that we think mirrors Dalle’s earlier scene with the boy—he gets up and runs into the bathroom locks the door, and masturbates furiously to his own reflection until he empties himself into the mirror while his wife pleads with him from the other side of the door.

The mirroring between the two couples doesn’t end there. Gallo still taken over by his bloodlust, and unwilling to trust himself in his wife’s control—disappears from her for a night and a day. He roams the french subways creeping on women, before finally settling on one of the maids at the the hotel who he attacks, rapes and kills.

It’s interesting to contrast this with the boy who Dalle eats. With Dalle it is the boy who has broken into her house, and come into her bedroom with the desire to fuck. Prince Charming in some ways, simple house burglar in another. But the contrast is quite striking. Gallo when he goes after the maid invades HER space. He attacks her. Dalle manipulates this same kind of male invasion to bring men to their bloody end. Even though Dalle and Gallo are both ostensibly murdering innocents—the nature of how their predatory instincts work is completely opposite and completely entwined. In the end, these innocent people, male and female are all dying because of this cycle of male privilege of female space. It infects us all.

Beyond all of this though is the pure aesthetic of a bloodied Dalle walking across a bloody mural down the bloody stairs—Dalle descending the stairs is one of the most brutal and harrowing things you’ll see. And the way Denis frames it with Gallo watching broken in the shadows—seeing in her, his own sins and his own horrifying end. But as with Descas he can’t accept it. And after choking out Dalle and leaving her to the flames she has desired all film, he retreats back to his wife, and his own hellish future that he knows is coming, but refuses still to accept. And we know that, as with Descas, there in the flames waiting for Dalle, Gallo will drag this woman he loves down with him as well.

Further reading: The Cages of Pretty Deadly