Daisuke Igarashi is one of the strongest storytellers in all of comics. Reading Igarashi is the sole comic reading experience that actually equates to the sensations of watching a Tarkovsky movie. And like Tarkovsky the core strength at play in Igarashi’s work is the sculpting of the miraculous. The ability to contextualize a happening within a narrative which itself transcends that narrative and creates for the reader the sensation of the sublime. A good example of this would be the bell scene in Andrei Rublev. Or the candle scene in Nostalghia. The scene with the witch in The Sacrifice.

I’ve thought about a couple of different ways to tackle explaining how this works within Igarashi’s work, one of which was through his work Children of the Sea–which is notable within Igarashi’s canon, because it is his longest story, and it is the only one available to buy in English. It is also impressive because in Children of the Sea Igarashi is able to maintain the same power of his short story anthologies–he still is able to create the same collection of miracles within a single sustained narrative. I have only read the first two volumes so far though, so my take on it’s strength vs. his other work is incomplete so far at best. And it is so massive, when you are talking about the mechanics of these miraculous supernatural narrative events, it is almost two wide of a geography to really make much sense, particularly if you haven’t read the work.

So instead I’ve chosen to focus on a shorter story by Igarashi in the hopes of better isolating the mechanics which create the space for his miracles(and by virtue…steal it for my own work, HA). The work I’m going to focus on is his short story Spirits Flying in the Sky from his anthology Soratobi Tamashii.

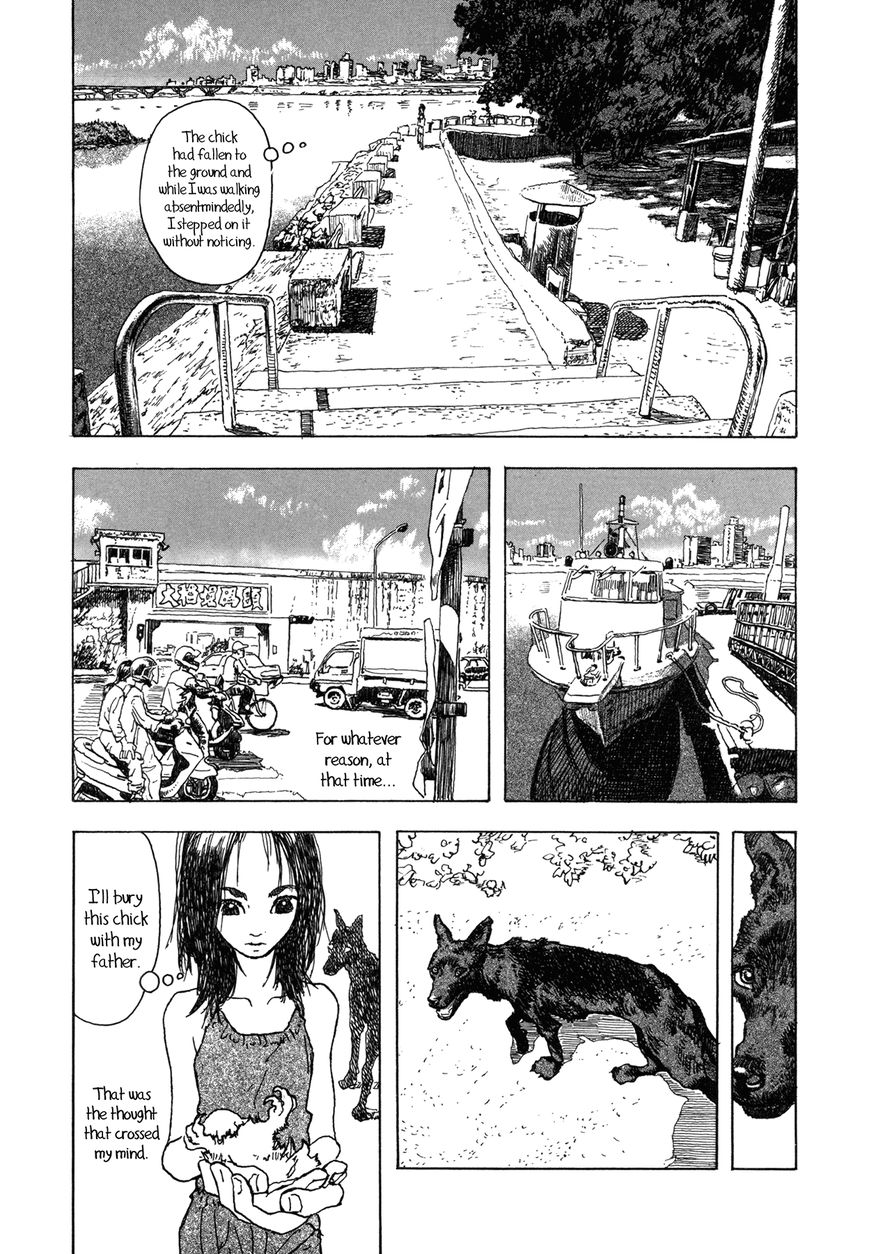

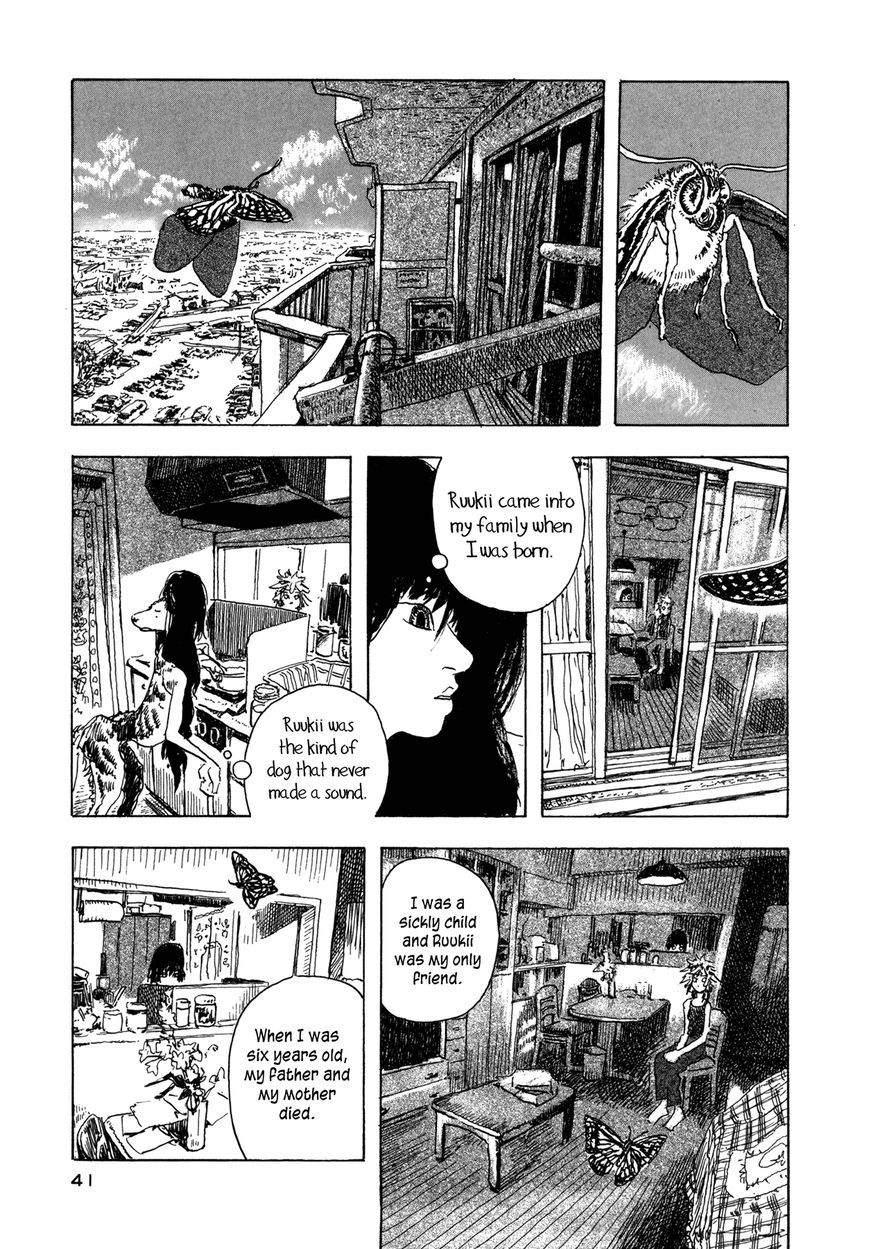

The most logical starting point for unpacting Igarashi is his style itself. You see a lot of the tenets of Igarashi’s style in the above image. His line itself is a soft, wavering line, which in and of itself allows for the borders of the worlds he creates to slip ever so slightly. For Igarashi, form is not the unwavering dictation of a set system of symbols. Rather, symbol is simply that symbol. And in that way, it is always contextual to the moment created. In this moment, Maki’s large hand that bends and contorts gaining in texture and detail to her face which is emphasized in detail by greater and greater degrees of it’s rendering. On another page, the effect could be the complete opposite. All artists do this to one degree or another, but few have this as a function within their greater abilities as a storyteller. Igarashi’s art allows for a slight power of suggeestion to reach in. As if Igarashi is merely hinting at an idea, so that he allows for you to come in and fill in the rest. His idea of a body, meets your idea of a body, and you become bound by that transaction. His style is an invitation, where many artists, particularly in the west, see their art as a dictation of terms.

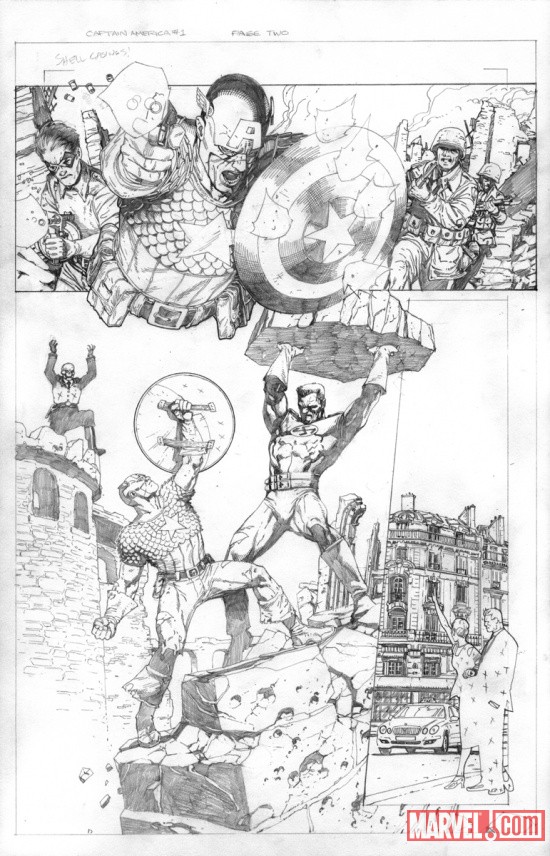

Steve Mcniven’s shield is a shield, rock is a rock, this is how a torso looks, here is a row of houses.

Look at the way that Igarashi’s boat bends, or the way the buildings in the background suggest buildings. Maki’s tank top is a form unto itself, the dog whose body is made up of a multitude of arcing shifting lines…this is the idea of a dog. Or more it’s the representation of the idea of the idea of a dog. Art as the externalization of internal symbols against the impossibility of a shared reality. The ruse that you could ever actually draw a dog, or that realism exists in any form and isn’t the last refuge of liars. Igarashi with his forms is communicating with the ideas behind the ideas, by allowing the vulnerability of the shakiness of his own perceptions to flood into his art.

Igarashi at the end of the day isn’t really about form. It is only in the sense that it isn’t. The focus of his style is actually texture.

Texture is the sensation in art of something that you can feel with your eyes. It invites the reader to consider how a collection of lines may feel. Where form is a dictation, a drawing up of borders, texture is the invitation of the reader to fall into the page. There are an almost infinite number of kinds of marks that Igarashi makes in his work to create different textures and sensations–but where it gets interesting, and ties into his ability to craft the miraculous in his comics, is just what it is that he is putting all of the effort into in terms of texture. Rarely in a Igarashi comic will you see much texture put into the human body. Even clothes are only a few degrees up. But when it comes to animals, nature, and the surrounding world, Igarashi is a line spitting fool.

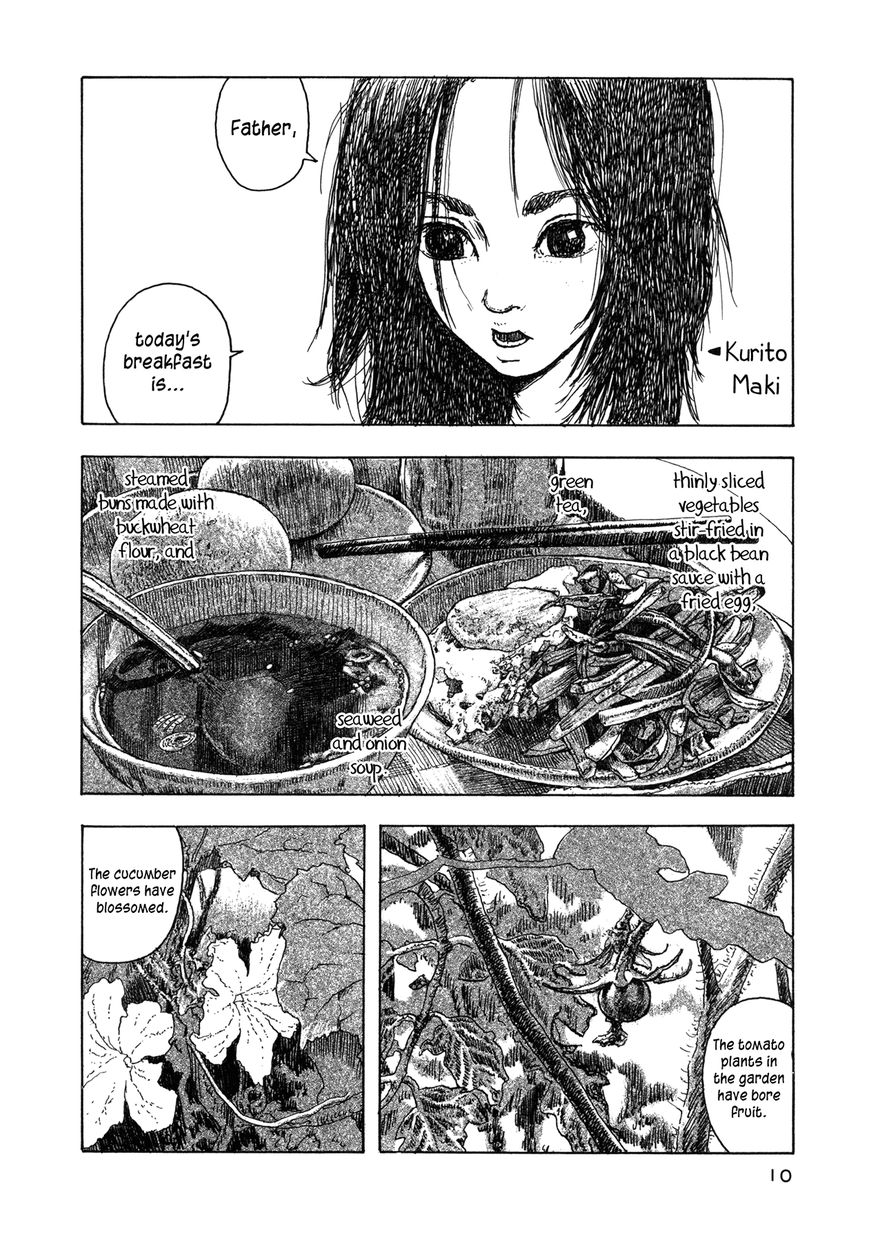

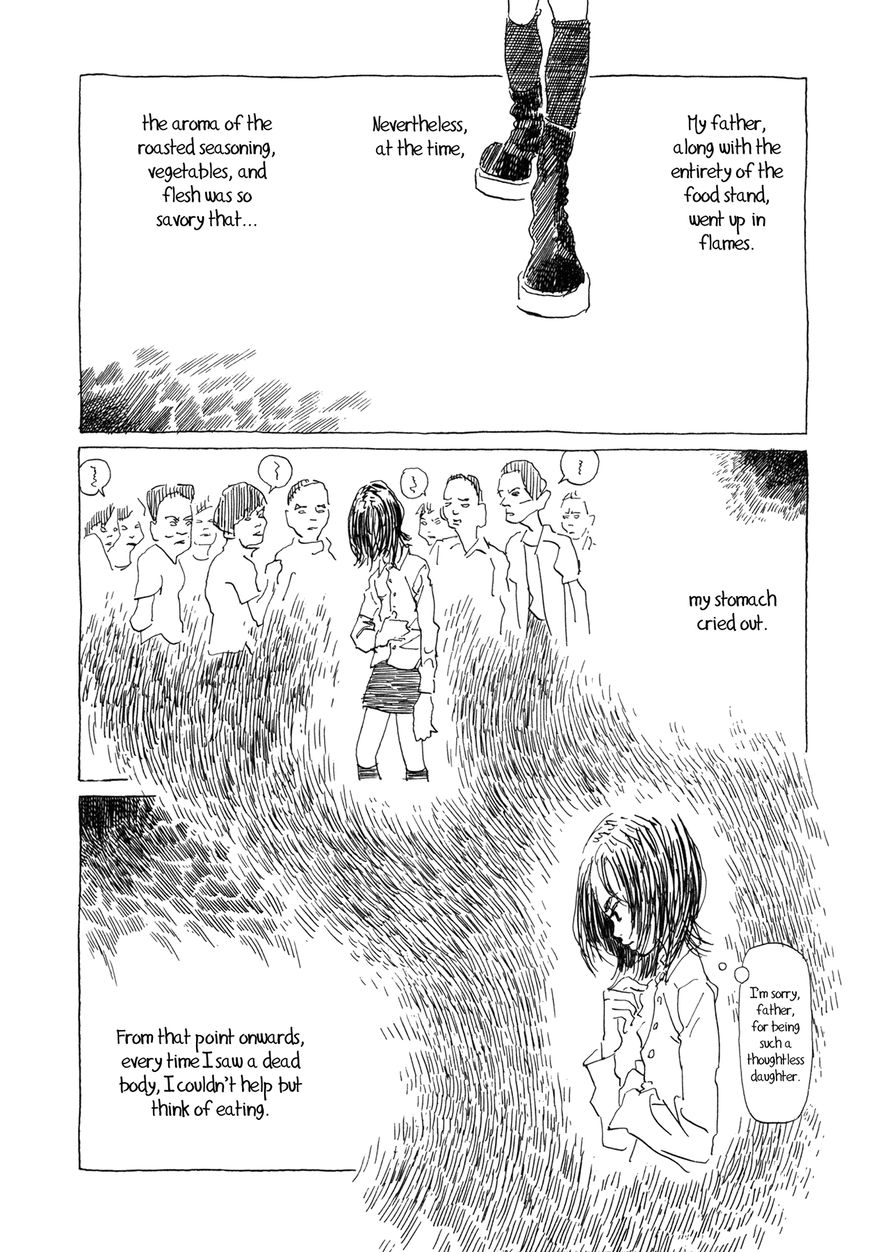

Compare in the above page, the difference in texture between Maki and the food she desires, and the garden the food has come from. It is clear where Igarashi is putting emphasis.

There is a displaced focus at play in Igarashi’s work.

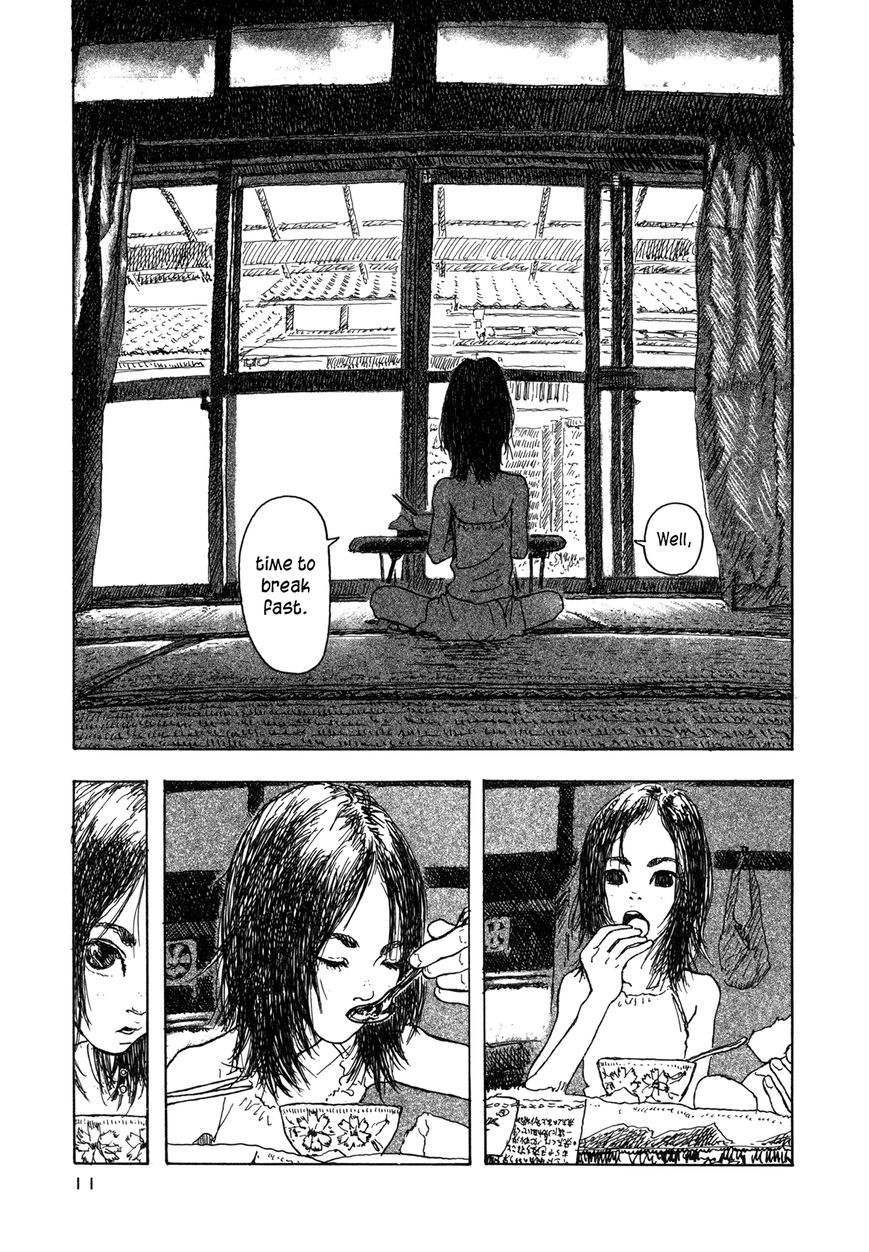

When characters are directly observed they are mostly engaged in fairly mundane things, like eating breakfast. But in intense emotional moments of introspection, Igarashi’s focus is on the world around them. He makes their concerns echo in their smallness compared to the breathing world around them.

In this scene, Miyako is talking about the deaths of her mother and father, but Igarashi instead focuses on the butterfly as it flies into the room. And furthermore, he obscures Miyako as she is talking behind a kitchen counter. We see the side of her face when she starts to tell her story, then we see her back, and Ruuki in profile but distance. And then the last two panels when Miyako is describing the trauma of bother her own illness, and the death of her parents, which forged her bond to Ruukii, she couldn’t be more obscured by Igarashi. There is a sensititivity in this kind of storytelling technique, because it gives emotions such an incredible weight that as a reader you aren’t allowed to engage with them directly. It is a way to draw out pain, to extend it’s moment–pain and emotion is extracted not at a knife point, but like a bow being pulled across a cello. You can hear more than is said here. This is the creation of space for emotion to be evoked.

This displaced focus allows for a binding to occur between the emotions of its characters and the mysterious sacred spaces around them.

I actually picked Spirits Flying in the Sky, because the story is itself literally about the binding between repressed emotions and mysterious spirits of the divine. But all of Igarashi’s work has these elements at play in them. In Children of the Sea, we see the mysteries of Zora externalized and bound to the nature of a weeping sea turtle burying its eggs on a beach for the first time. In the short story Spindle, which makes up the bulk of Witches, the witch Nicola, despite having all of the secrets of the world at her disposal, has externalized the mystery of her emotions into a own prison seen through her inability to perceive a single little girl.

In Spirits Flying in the Sky, there are two primary miraculous moments. I am going to focus on the first one and show how it demonstrates the elements I’ve described to this point.

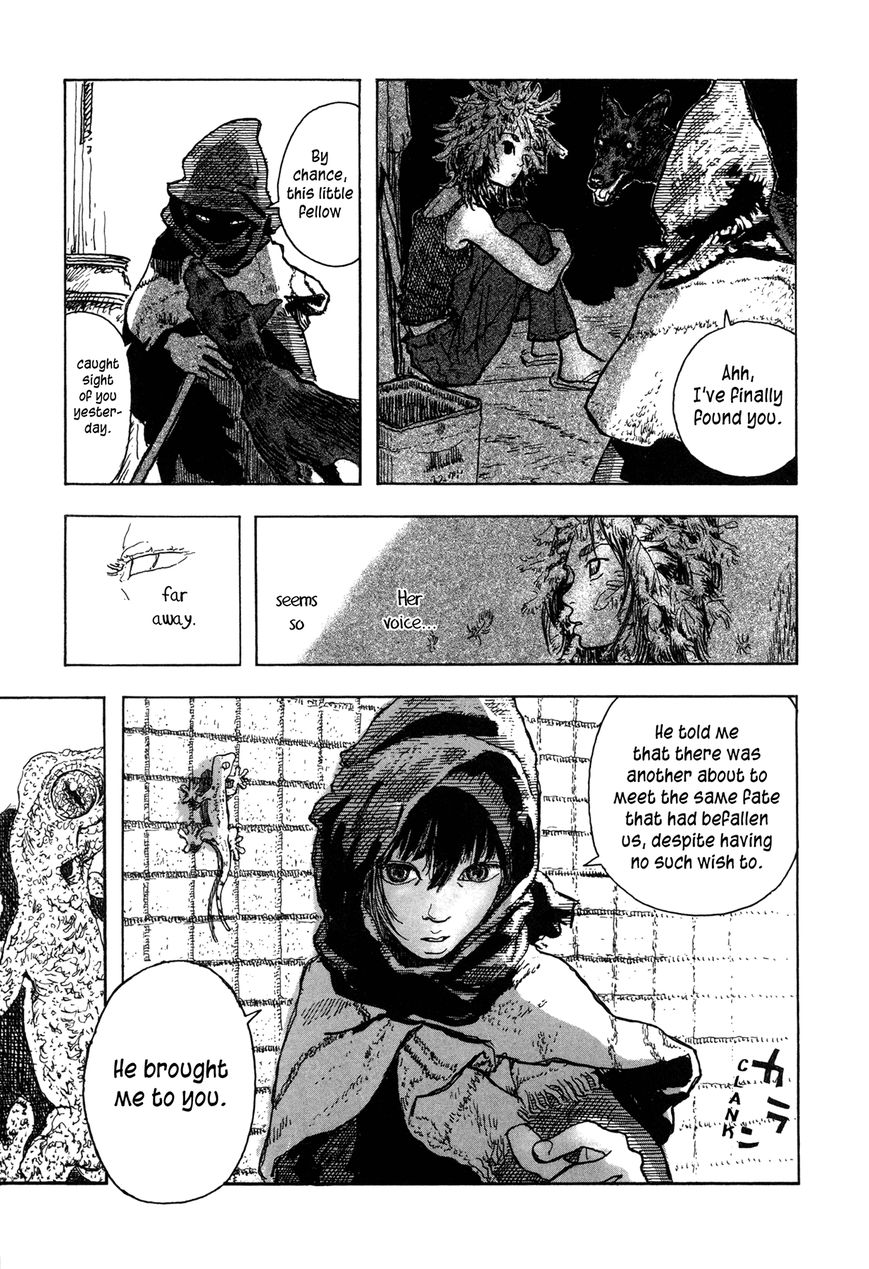

Notice in these opening pages, even though we have a myserious stranger who has arrived, and that the narrative structure is focused on her, Igarashi displaces that focus through the Lizard on the wall. It is through that lizard that we enter into Maki’s repressed memories about the death of her father. And notice how as we reach deeper and deeper into this sacred place that Maki has within her, Igarashi’s forms begin to degrade and break down.

Also notice how the dog that was just sort of randomly in the panel in the page way above, is now back and a critical story element. This happens routinely where a natural element that focus has been displaced into, returns to perform a particular function within the lives of the various protagonists. It is a different way of seeing the world that Igarashi is imparting. An inter-connectedness of all things, even the smallest most innocuous things have roles to play within other more complex experiences.

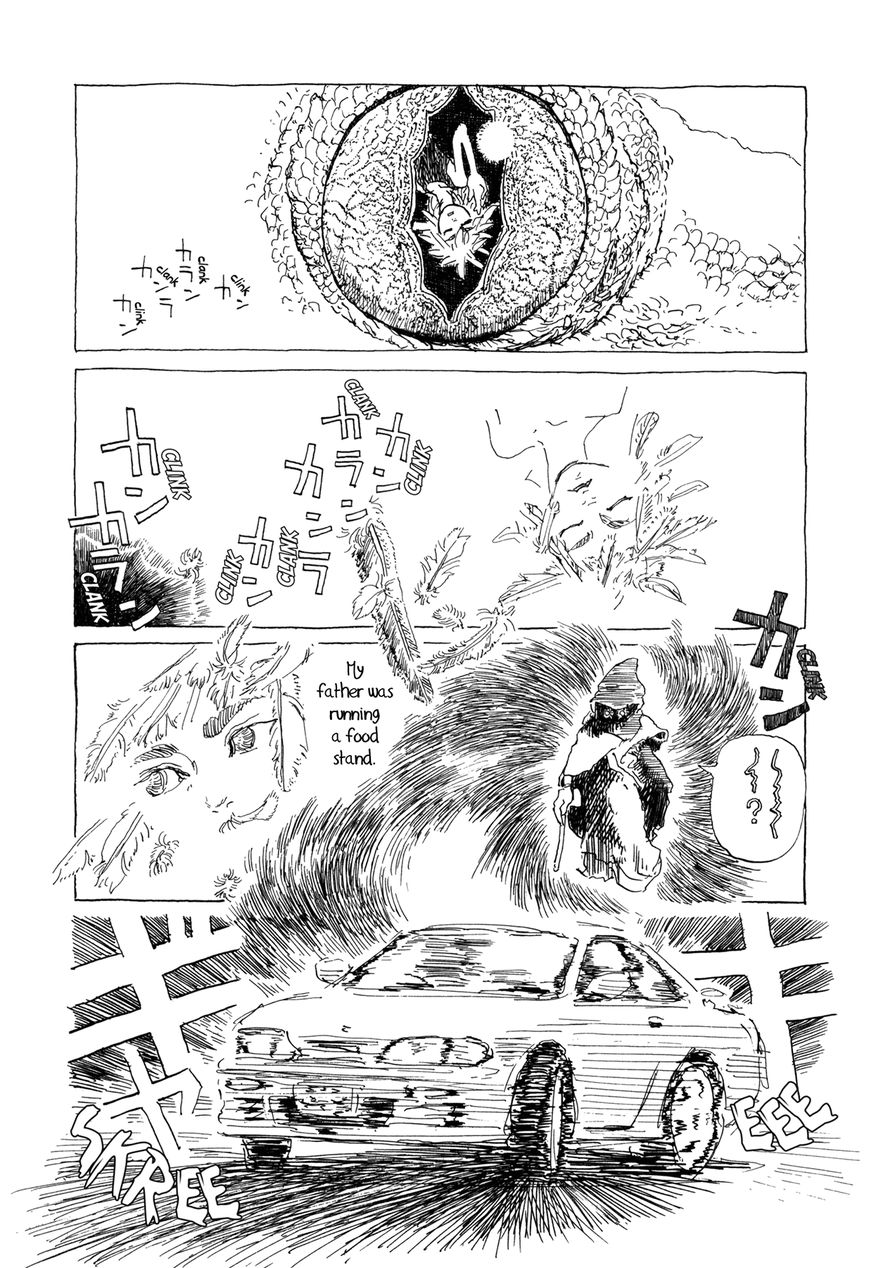

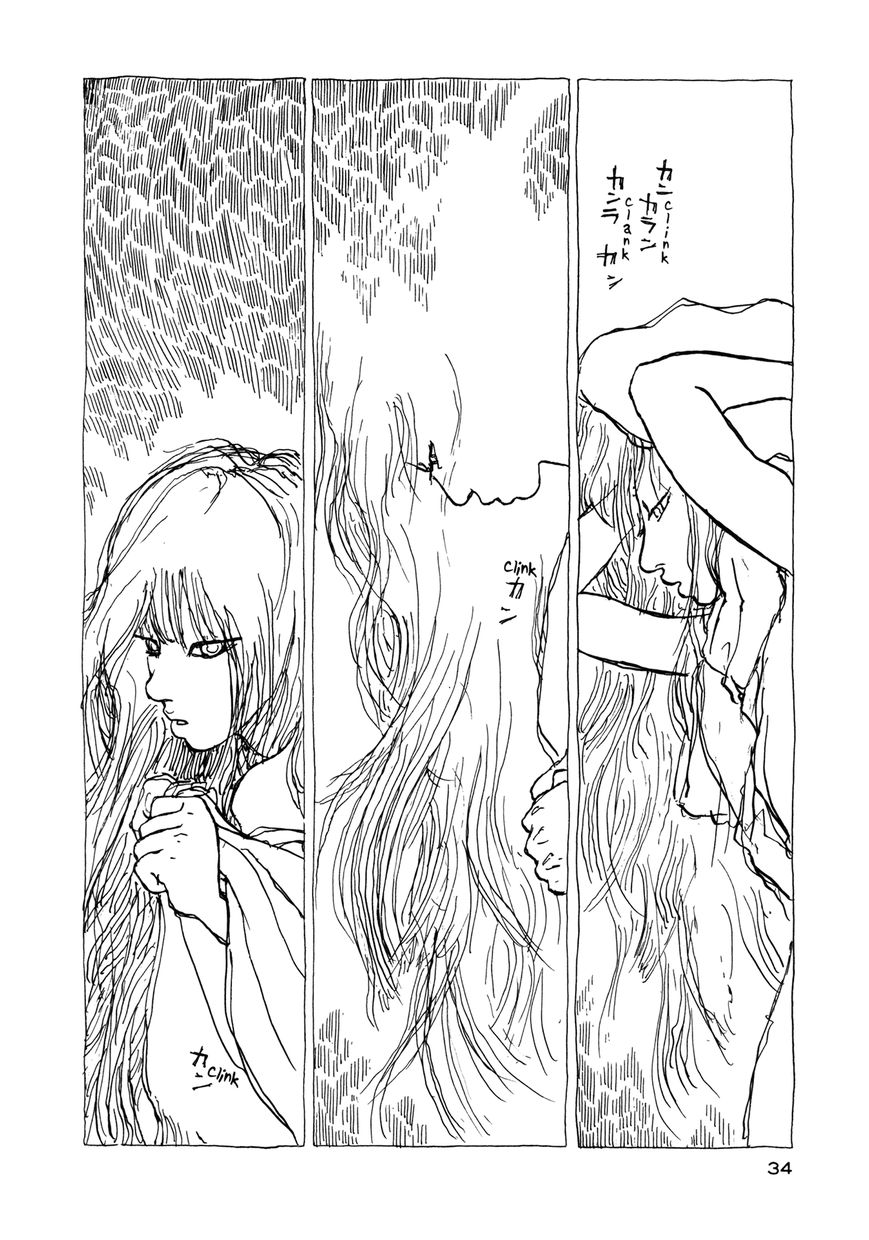

Notice now even the formal comic structures of the page have broken down into a montage of images. Also the key component of what is happening here dramatically is the act of confession. In a comic, where the protagonist isn’t ever directly allowed to express her grief over the loss of her father, this is a veritable explosion of emotion played out over three pages. And in contrast to how Igarashi normally deals with emotions, it isn’t displaced anymore. The focus of the page spirals more and more onto Maki. Underlining her act of confession. Her unburdening of pain. The ecstasy of relief comes directly from the tightness of the restrictions beforehand. All of the displacement and binding that occurs around this moment is lessened and in that space Igarashi moves the inexplicable, the supernatural, and the sublime.

Look at these lines, as Igarashi seems to almost say “this is beyond the ability of line to contain. Even as he changes the page rules back to a paneled structure to contrast with the previous montage/catharsis. There is also a building action in this page as Miyako reveals herself in a diagonal designed to pull you into the next page.

This is the sublime moment, the nexus of beauty and horror, the awe of that moment is so great that rather than have the whole page just be the image on the right, Igarashi has us literally look away with the next panel. Avert your eyes.

And this isn’t even the climactic miracle of this short story.

The pages immediately following have a liminal quality, characterized by the bending angles and constricting walls of the space Maki hesitantly moves through. Igarashi is extending the moment as he softly lets it bleed out. And Miyako steps from the spirit world of the sublime into the mundane reality of the world of the story.

Now Miyako has come into form, and this sets up the acts leading up to the final miracle in the story. This is centrally the creative balancing act that powers Children of the Sea as well and what allows it to be a continual series of cathartic sublimity rather than a work only fixated on the building up to a singular moment(even as the smaller miracles all build upon one another to greater and greater climax).

What you are looking at centrally with Daisuke Igarashi is someone who knows how to structurally displace, and distort emotions within constructed narrative cathedrals–how to bind and channel those emotions into supernatural moments that connect even beyond their singular value as singular images. What is weird reading Igarashi is that he is an artist that you actually have to legit read to really get. While his artwork is pretty on it’s own weight–to really understand the weight of what he is doing in his work, and the level of mastery with which he executes his comics, you have to hear the music he is playing. It’s like…a drop doesn’t make sense by itself, it is all the music that leads up to the drop, and what comes after the drop–even as everything before and after are beholden to that drop. This is a floating action. With Igarashi that space is filled with a kind of occult naturalism that hits at the very basis of the idea of the supernatural. But it is a mistake to think that the moment is special because of only what is within it, and in focusing solely on that, to lose that the moment was constructed by the first breath and the last breath, the things that came before, and the things that came after. And on some level all I’m talking about is the central idea of a climax and how it is executed within comics as a whole–there are moments that are special within something like Naruto that are functionally built in a lot of the same ways, specifically in terms of the management of emotions and their binding to spectacle.

But with Igarashi there is a particular richness that pervades beyond simply the moment, and exists within the microcosm of his linework, and overall composition as well as the macrocosm of his overall focus as an artist within the sacred spaces of the unknown that exists perpetually just out of reach all around us. Igarashi is fundamentally an artist not interested in explaining the inexplicable–but merely creating it. And within the sublime amazing that is the experience of his work, is the joy of comics as a medium that are literally capable of anything. Igarashi is one of those artists that is comics-affirming. For me personally, my experience with Igarashi, and it’s not important to anyone but me, but for me, reading Igarashi is to be filled with an uncontainable love. And such that I can explain it to others, is probably very little. Oh well.

Ha. I’m literally like spending my week checking the mailbox everyday for the last 3 volumes of Children of the Sea. I’m a dork.