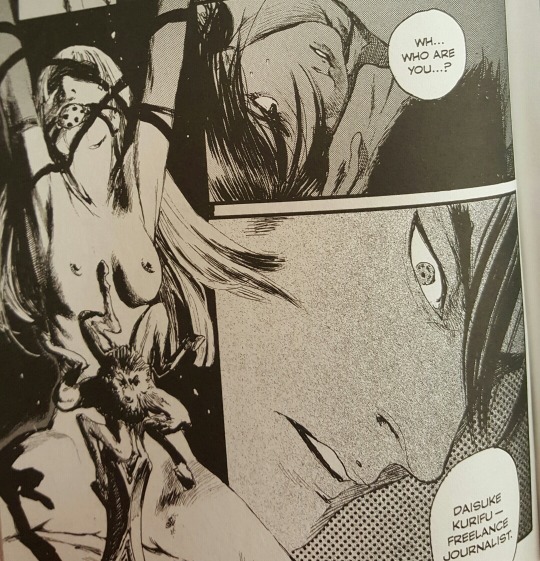

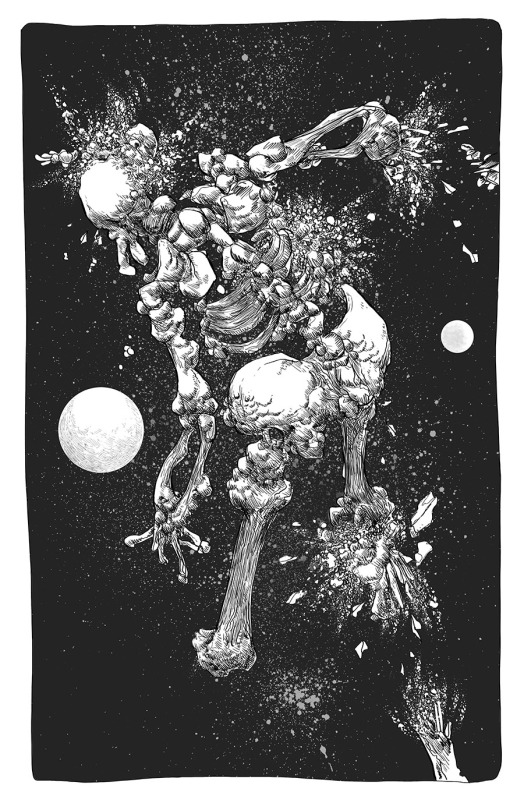

The most immediately striking thing about Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame! While reading it is the dungeon crawl dread of it. The book follows Kyrii(also called Killy in earlier editions) as he crawls up an endless sprawl of technological ruin. Nihei more than any other comic artist plays with scale. Closed claustrophobic spaces opening into giant caverns. Small guns, large mile long blasts. Dramatic pull aways where Kyrii becomes just an ant moving up the spin of a dead cyborg god. Even though a lot of the mythos of Blame! Forms the foundation for all of Nihei’s work afterwards. Blame! Is the basic formulas of Nihei’s storytelling at their most primordial and most direct.

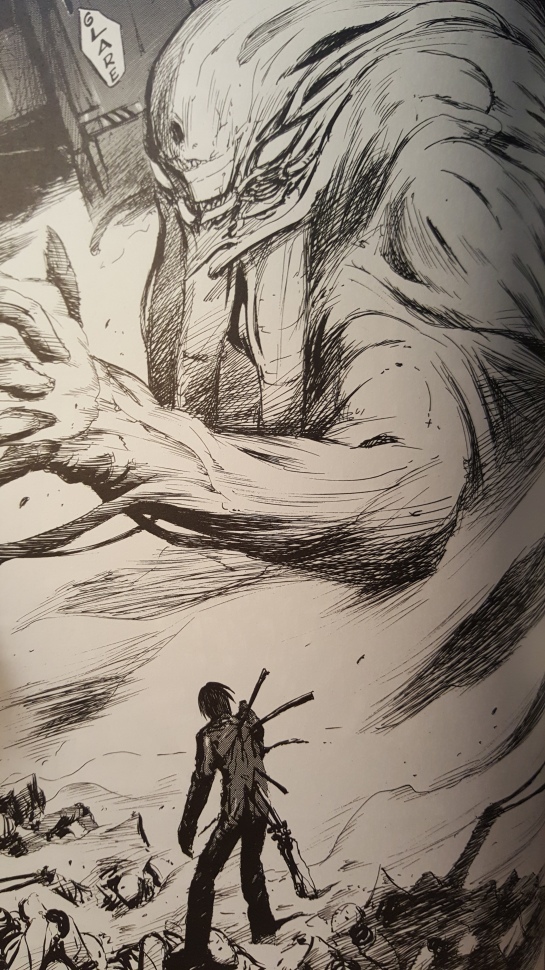

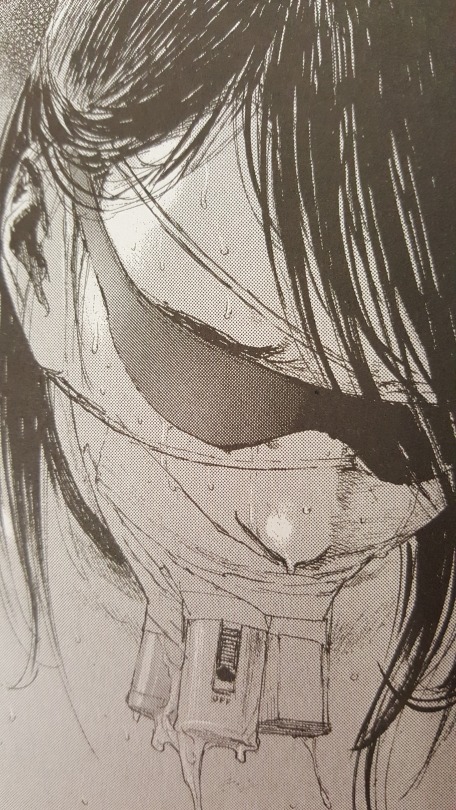

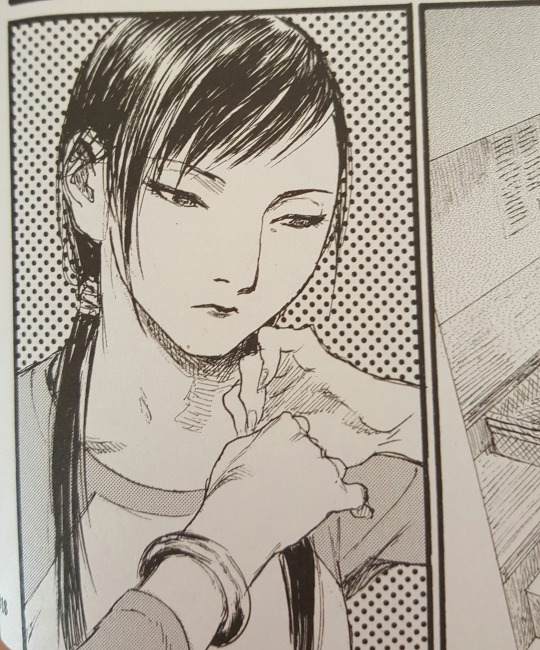

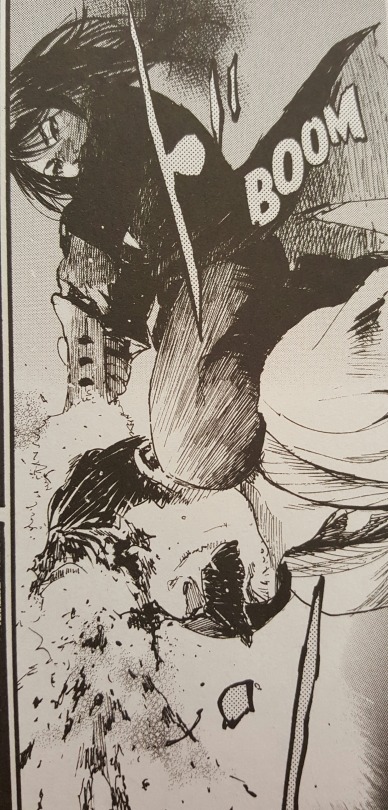

Kyrii searches for thousands of years for the net terminal gene which will connect humanity from the base reality that is corrupted by insane machines and cyborgs eliminating humans on sight. Much of Blame! Works along these basic cycles: Nihei climbing silently around, through, and up mechanical ruins. Encounters corrupted mutated human populations. He searches for the net terminal gene. The safeguards show up. Kill all of the humans. Kyrii kills some of them. Then he keeps up his journey. The unrelenting repetition of Blame! Is key in building the dread of the book. As a reader you figure out pretty early that this is a dungeon you can’t escape from. So it makes the few moments where the book opens up into grand vistas, or dramatic fights between Kyrii and the safeguards all of the more dramatic. It makes the existence of Kyrii, Cibo, and the fallen humans all the more tragic. The architecture and the design of the world is along the lines of Giger’s Biomechanics, so some of the appeal as well is just the spectacle of what Nihei draws on one page or the next. His capacity for continually upping the ante in design and scale is really incredible in Blame!

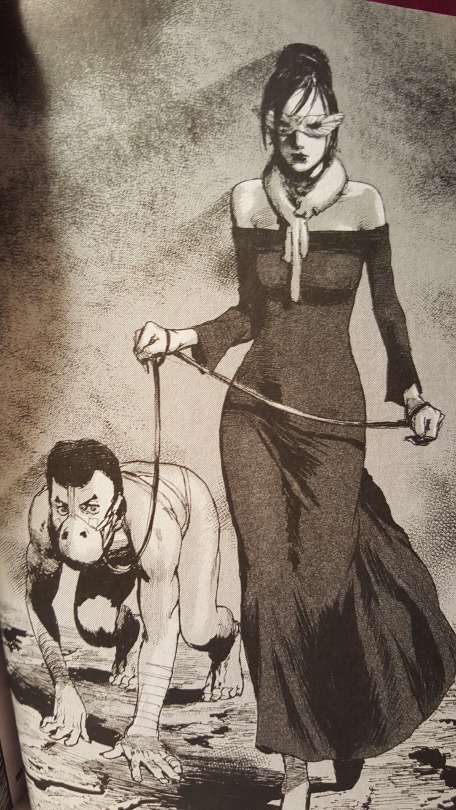

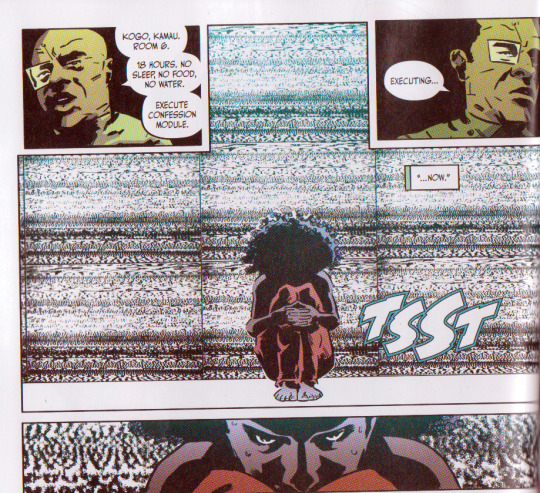

What’s interesting to me on this reread though, is the way that the microstructures of the world in Blame! Are suffused with the flaws of the greater cosmos. To understand Blame! You have to understand that there are kind of three tiers to it. There is the base reality which is the zone where humanity lived and built these machines, programmed all of these various rules, and where the second tier, the netsphere was created. The netsphere is where all of the programming for the machines in the base reality reside. The third tier is the space between the netsphere and the base reality that the safeguards move between. The safeguards are these terrifying cyberpunk hellraiser looking demons that exist to enforce the rules of the netsphere within the base reality.

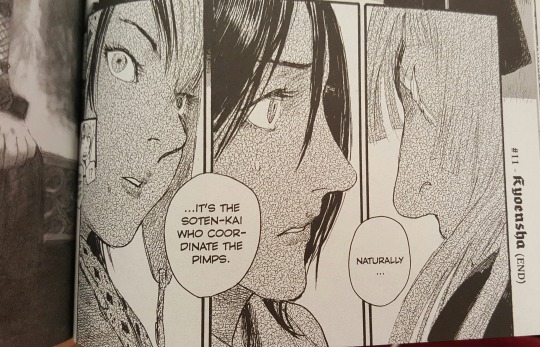

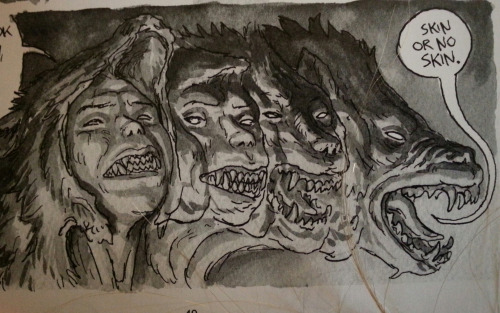

Something you find out in the prequel series Noise is that the netsphere, the reason only those with the net terminal gene can interact with the netsphere was that it was a way for humans to segregate those who had power to connect versus those that did not. This human class warfare presented an exploit for the safeguards to pervert. So once the netsphere rules were altered to send the safeguards after the humans, it just became a matter of exterminating all of those with the net terminal gene, so that the humans could never access the netsphere for long enough to save themselves from the safeguards and builders. The insane builders are why there is this endless technological sprawl. They can’t be stopped from building, so they just mindlessly continue to maintain this huge superstructure which imprisons humans. And humans thousands of years removed from this catastrophe exist under the suppression of the safeguards, removed from the netsphere admins who are functionally God of the base reality. So you can see the genetic structure of humans breaking down because of inbreeding and flawed cloning technology that they’ve lost the knowledge of how to repair or rebuild. As humans break down they either move toward the safeguards in evolution or seem to devolve into sewage.

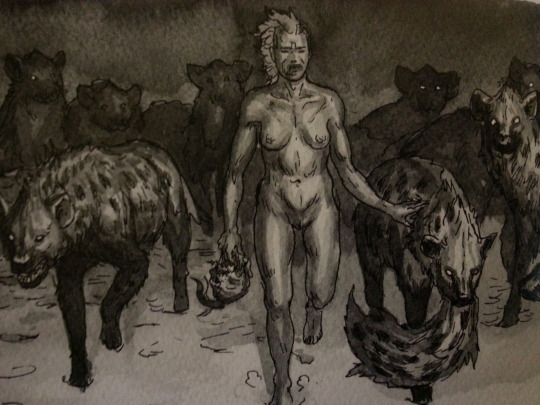

This aspect of being both withdrawn from god in the netsphere, god’s absence, human’s fall–while every aspect of their reality is simultaneously controlled and is an avatar of that withdrawn god. The architecture is literally the design of this netsphere programming. It’s randomness. It’s chaos. Is design. The safeguards themselves as fallen demons, seem corrupted by their continual interaction with these humans. They become more human. Jealous. They take on personalities. Filling the void of vacated humans. It is apocalyptic hell on earth. Techno-apocalypse.

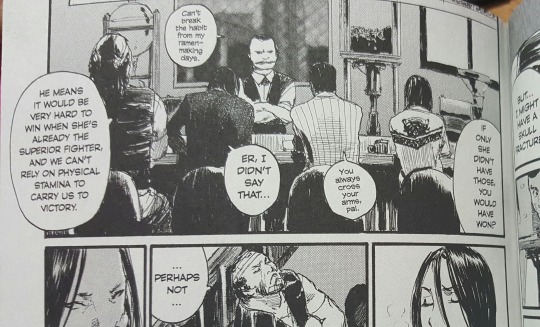

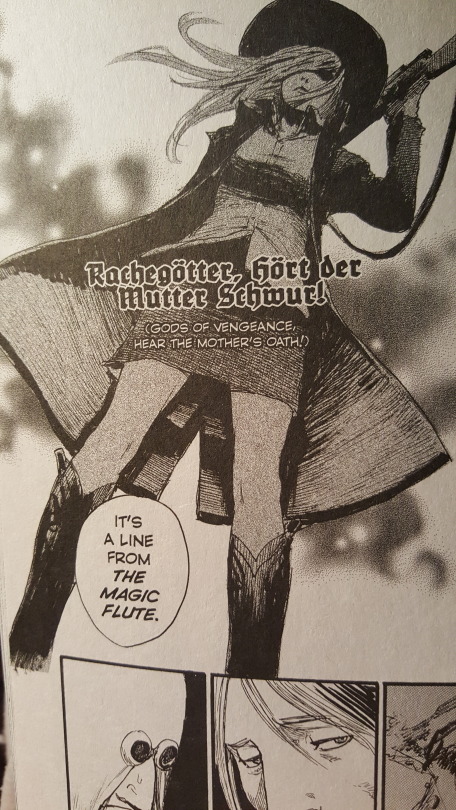

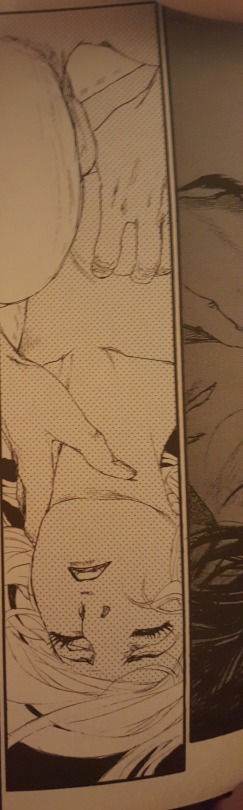

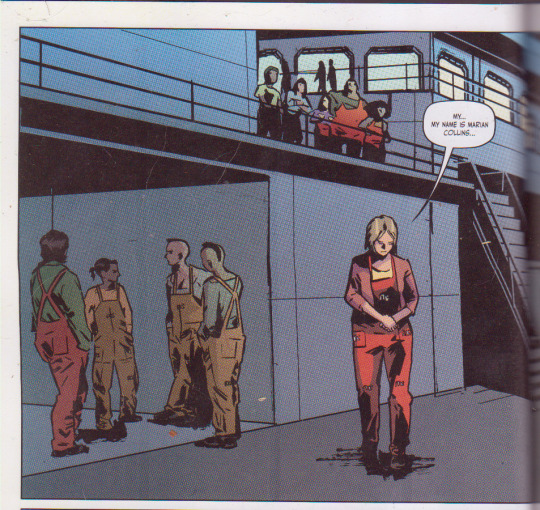

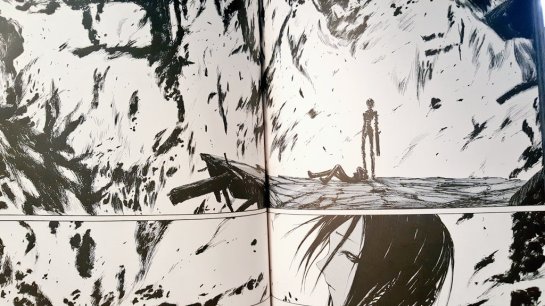

So in volume 2 of the Master Editions that Vertical have been putting out, there’s this great moment toward the end of the book, where Kyrii and Cibo are trying to defend the last of this group of humans against an unholy assault of safeguards both in number and scale. We get these micro battles between the humans, kyrii, cibo and smaller safeguards, and this huge kaiju like battle evoking the old ones between a giant safe guard monster and a builder that Cibo has hijacked. So on one level you have this tribe of humans fighting off these basic safeguards. On another level Kyrii is fighting this super demon angel safeguard Sanakan–occupying this space of demigods. And then beyond that is the space in between the netsphere and the base reality that Cibo has hacked into which is like a lesser ring of heaven, where an admin has descended to guide her. And she’s fighting the safeguards in this almost immaterial space. That also manifests itself in the base reality battle. So these three tiers are all moving around at the same time as Nihei zooms in and out at extreme distances while everything around is bathed in fire and metal and leather. At one point Sanakan actually takes on the aspect of a dragon almost in her fight against Kyrii invoking the earlier heroic cycles of knights and dragons, as well as ragnarok. Nihei is interweaving multiple cosmos while showing simultaneously the unimaginable scale of the battle happening across three realities AND how small it still is within the greater whole of Blame!. This is only the second volume of the omnibus editions!!! There’s a few battles later in the series that are even larger in scale than this one. And even this battle everything feels lost, nothing is saved, and there is only more ruin and despair. Kyrii is knocked back. And then just starts the climb back up. There are no comics that are like Blame!. Even Nihei’s later work which is also excellent. Particularly Abara and Biomega. I mean it makes sense that there’s no reason for Nihei to just keep making Blame! And the themes and basic structures of Blame! Are present in all of his work–but this cyclical saga of technopunk despair is a one off. And there’s nowhere else in comics to go for this fix. This is comics at its most spectacle. It’s fun to read Blame! In this kind of instagram world we live in now. Because since it is so many moments of “oh shit, look at that” there’s a way that reading it now is like touring it with friends. These are snapshots from my Giger vacation. Reading Blame! Is like going to Rome. We should all aspire to make something so jawdropping and singular.